Seven vulnerabilities affecting Dnsmasq, a caching DNS and DHCP server used in a variety of networking devices and Linux distributions, could be leveraged to mount DNS cache poisoning attack and/or to compromise vulnerable devices.

“Some of the bigger users of Dnsmasq are Android/Google, Comcast, Cisco, Red Hat, Netgear, and Ubiquiti, but there are many more. All major Linux distributions offer Dnsmasq as a package, but some use it more than others, e.g., in OpenWRT it is used a lot, Red Hat use it as part of their virtualization platforms, Google uses it for Android hotspots (and maybe other things), while, for example Ubuntu just has it as an optional package,” Shlomi Oberman, CEO and researcher at JSOF, told Help Net Security.

The vulnerabilities and possible attacks

JSOF researchers unearthed seven vulnerabilities: three allow cache poisoning and four are buffer overflow vulnerabilities, the worst of which could lead to a remote code execution on the vulnerable device (if Dnsmasq is configured to use DNSSEC).

Collectively dubbed DNSpooq, these vulnerabilities (CVE-2020-25681-7) can be combined to build extremely effective multi-staged attacks, the researchers noted.

Combined with other recently disclosed network attacks – e.g., NAT-slipstreaming by Samy Kamkar, Sad DNS by researchers at University of California Riverside, and maybe also lack of Destination-Side Source Address Validation (DSAV) discovered by researchers at Brigham Young – they could likely lead to much easier and more widespread attacks, they added.

The researchers confirmed the viability of several different DNS cache poisoning attacks (described in detail in this paper):

- On open forwarders (approximately 1 million Dnsmasq servers listening openly on the internet)

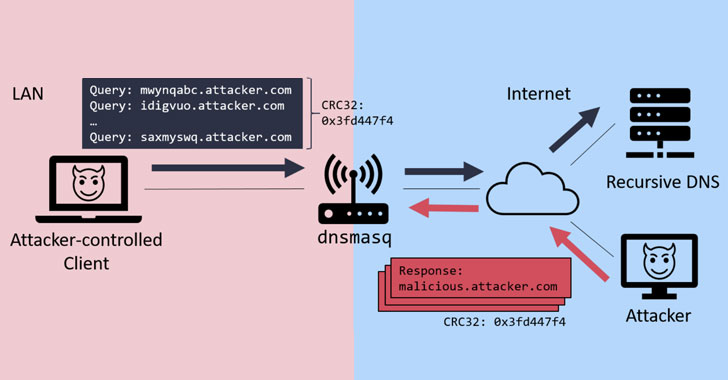

- On Dnsmasq in LAN from browser

- On Dnsmasq in LAN with attacker-controlled machine

It’s also possible to perform DNS cache poisoning if a Dnsmasq server is only configured to listen to a connection received from within an internal network, but the network is open (e.g., an airport network or a corporate guest network).

Depending of the number of devices/systems that have been injected with fake DNS records via these flaws, attackers could also mount DDoS and reverse DDoS attacks.

The four buffer overflow vulnerabilities are present and can only be exploited if Dnsmasq is configured to use DNSSEC.

“The vulnerabilities can be triggered by sending a crafted response packet to an open request (frec). This can be combined with the cache poisoning attack to potentially mount a remote code execution attack over the device running Dnsmasq,” the researchers explained.

Vulnerable versions, devices, and mitigation advice

The researchers confirmed that Dnsmasq versions 2.78 to 2.82 are all affected by the vulnerabilities. Whether a device/system is affected or not (or just partially) also depends on how it uses Dnsmasq.

They found that some Cisco VPN routers are affected by the DNS cache poisoning vulnerabilities, and so is the OpenWRT firmware available for hundreds of devices and models.

Devices that do not use Dnsmasq’s caching feature will be much less affected (but not completely immune) to cache poisoning attacks, Oberman told Help Net Security. Devices that don’t use the DNSSEC feature will be immune to the buffer overflow attacks

“DNSSEC is a security feature meant to prevent cache poisoning attacks and so we would not recommend turning it off, but rather updating to the newest version of Dnsmasq (v2.83),” he added.

The researchers also advised on several workarounds that can be implemented if updating Dnsmasq/affected software or firmware is not immediately possible.

Among the vendors using Dnsmasq for some of their devices/systems are HPE, Aruba, Siemens, Tesla, Huawei, A10 Networks, Cisco, Ubiquity Networks, ZTE, and Google (among others).

The researchers coordinated their disclosure with most vendors through CERT/CC, so I expect the availability of patches/security updates will be communicated by them through a security advisory. Red Hat, Cisco, and Google were involved in the working group for the disclosure so they’ll likely have fixes ready to push out.

“All major Linux distributions also received the information under embargo from Red Hat in a dedicated mailing list so we assume they will also be issuing fixes at the same time. We assume that smaller and other downstream vendors will be issuing patches after that,” Oberman told us.

/https://specials-images.forbesimg.com/imageserve/6006561c5dcb9127247e5e89/0x0.jpg?cropX1=0&cropX2=3808&cropY1=96&cropY2=2216)