The Ministry of Defense of Ukraine Twitter is shown on a smartphone screen. A [+]

An interesting side-note to Russia’s unexpected invasion of Ukraine is that it may now be the “first Social Media War,” with individuals in the country being besieged able to share their real-time updates and videos from the frontlines. This ability to share updates and videos may help make sure that this war doesn’t end with the first casualty.

Reportage on Media and War

Since media intervention was the catalyst for its military actions, the Spanish-American War has been called “the first media-driven war”. Many newspapers published sensationalistic articles while reporters were dispatched to Cuba to experience the war.

The conflict in Vietnam was renamed the “first TV war” 60 years later. It became the focus of extensive news coverage because a large number of US troops were deployed to Vietnam in the spring of 1965. At the peak of the war in 1968 there was 600-plus accredited journalists who covered the conflict for US television, radio, and wire services. While the daily briefings of the Joint US Public Affairs Office were soon known as “the five-o’clock follies,” the war was frequently brought to American homes through the evening news.

In February 1968, Walter Cronkite – the anchor of CBS Evening News at the time and known as “The most trusted man in America” - made the bold statement that the conflict was “mired in stalemate.” Lyndon B. Johnson (then President) stated, “If Cronkite is gone, so is Middle America.”

The 1991 Invasion of Iraq – also known as the Gulf War – certainly made CNN a worldwide brand, and highlighted the power of cable news in such times.

First Internet War?

There is still much debate about what can be called the “first Internet War.” According to Wired Magazine, this distinction could be given to the Yugoslavian Civil Wars in the 1990s because it occurred with mass adoption of Internet technology and the birth online news outlets.

It was actually the 21st Century’s global warfare on terror (GWOT), following 9/11, that really showed how war can be covered in real-time.

War in the Age of Social Media

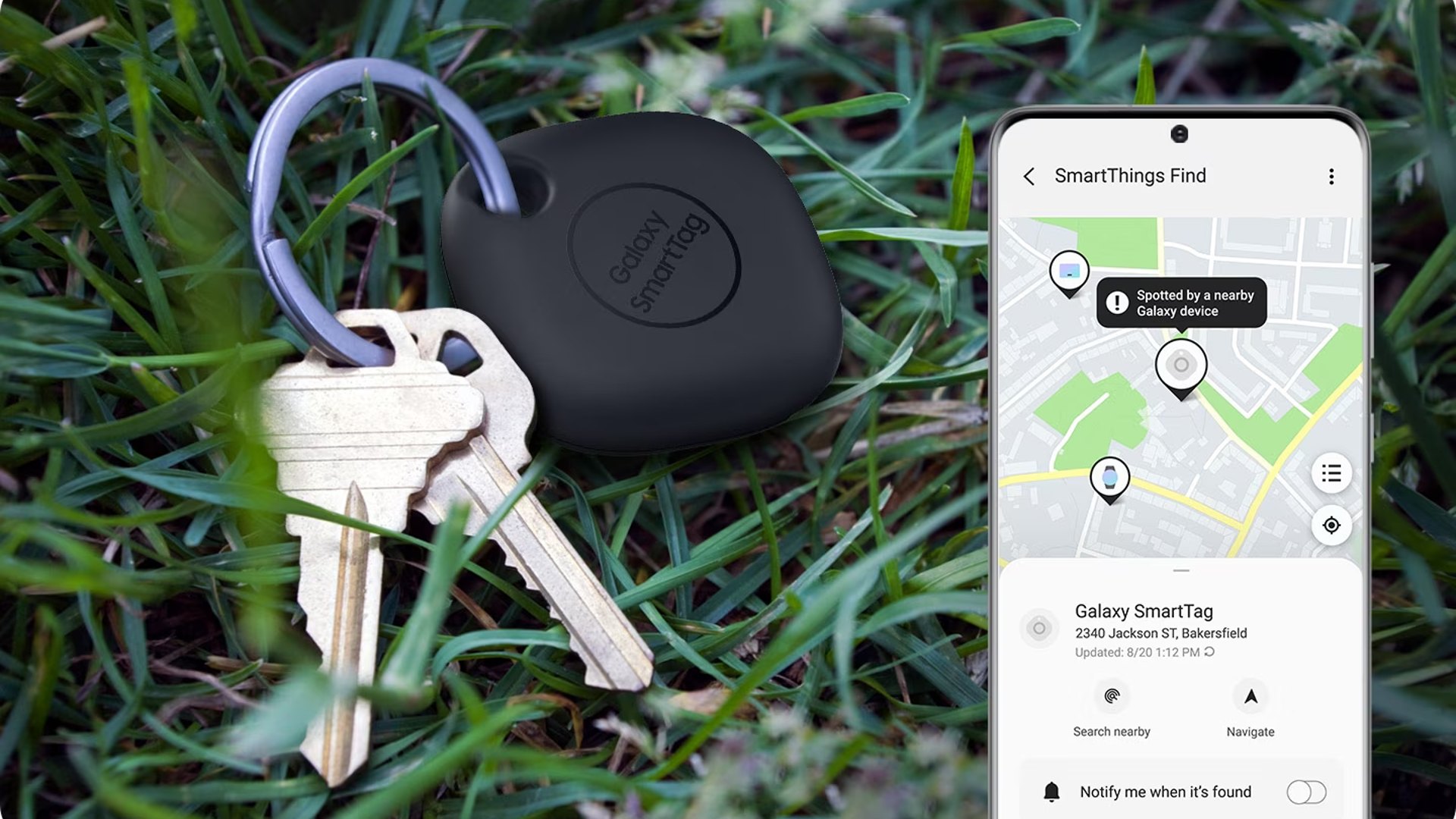

While social media is just beginning to be fully understood, the power of the medium could have a significant impact on news coverage. Ukrainians can stream live from the front lines and anybody with a smartphone, including Winston Churchill, Edward R. Murrow or Ernie Pyle. Walter Cronkite, Christiane Amanpour, and Ernie Pyle can all play the roles of war correspondents.

William V. Pelfrey Jr. (Ph.D.), professor at Virginia Commonwealth University’s Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, said, “Social Media represents a transformational component of armed conflicts, unlike anything that we have ever seen.”

“Historically, media depictions of war were either provided by the military – and therefore not likely to be representative – or derived from sketchy, smuggled materials,” Pelfrey explained in an email. High quality, real-time video can be broadcast from any phone at anytime on a social media network that allows for rapid sharing and re-tweets. This allows anyone to virtually feel the effects of combat.

Arab Spring to World War III

Many could see the Arab Spring events as a practice run for social media in covering fast-moving events.

Kent Bausman Ph.D. is professor of sociology for Maryville University’s Online Sociology Program.

Since the Arab Spring in 2011, social media was able to provide real-time information from the ground.

Pelfrey added that while Facebook has three times as many monthly users than it did ten years ago (and Instagram and Twitter have exponentially greater numbers) this means that the number of content providers (those people who are able to provide content) has increased and so is the reach. The society is used to reading news from other sources. Although journalists once provided all the coverage, today correspondents offer substantial coverage in difficult to reach areas or at times of violence. Our understanding of war will change due to the devastation and victim experience as well as images from live combat. History is written by those who win. When history is streamed live, the perpetrators, as in Russia, cannot rewrite it.

What is also different now is how social media isn’t being silenced by the Ukrainian government – as was the case during Arab Spring. It is actually a matter of trying to keep these platforms open.

Bausman stated that it is understandable why nations would wish to regulate social media in times of conflict. In the past, the narratives of conflict were controlled by the nation-states. All that has changed with social media. Â Furthermore, in the case of warfare, social media use might even be construed as a form of guerrilla tactics. One example is the hacking of Ukraine’s Ministry of Information by Russia. Although this could have paralyzed Ukrainian resistance, it was not reported at the time. Instead, social media provided the necessary communication gap. “President Zelenskyy was capable of taking to Facebook and communicating reassurance to Ukrainians.”

Many people around the globe are also using social media to express their support and sympathies.

Bausman suggested that it is possible to question whether support for this kind of situation would be available in real-time, given the fact that we rely on mainstream media reports. This is especially true in the US where many news organizations have abandoned keeping news divisions abroad. A lot of US media coverage on this conflict seems to have been sourced via social media. Evidently, social media has been a vital tool in obtaining on-the-ground reporting about dangerous events.

Misinformation can still be a danger.

Bausman said that the accuracy of reporting like this would be problematic. Bausman warned that there are many social media posts claiming to report on what’s happening in Ukraine, but these claims have since been disproven. Misinformation may be a catalyst for conflict. But its ability to convey real-time information and rally support could prove to be just Putin’s Achilles heal.