The terms SIEM (system information and event management) and SOAR (security orchestration, automation and response) are often used interchangeably. However, they are distinctly different applications and, far from being mutually exclusive, can – and often should – be used in tandem.

SIEM platforms have been around for many years and are the backbone of security operations centres (SOCs) for most organisations. The tools are essential for capturing log and event data from critical systems and producing system alerts and real-time dashboards when anomalies are detected. Significant fine-tuning and maintenance is required to ensure SIEM technologies remain alert to the most relevant (and accurate) risks.

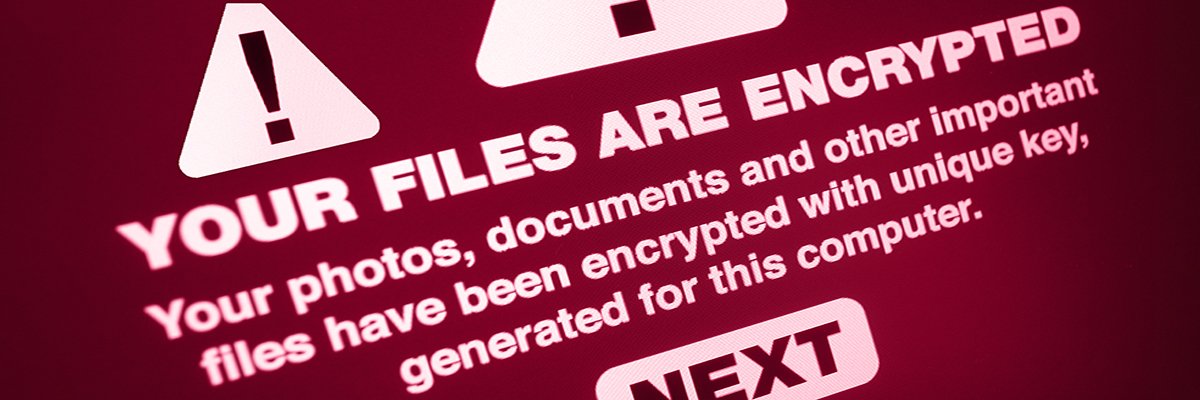

SIEM provides high-quality intelligence on threats and events, thereby enabling understanding of the protective measures that need to be taken. But a truly robust defence also requires the capability for some autonomous and consistent response. Enter SOAR.

The SOAR industry has grown exponentially over the past few years, with many businesses exploring the benefits of its applications. The critical element is the automation capability, which removes the need for users to carry out time-consuming and repetitive tasks, and frees up IT security professionals’ time for more specialised undertakings.

SOAR solutions need an element of integration with their SIEM counterparts to ensure they have the most complete picture of an apparent breach. For example, one user attempting to log into one application with the wrong password is not in itself an indication that the user has been breached. But the same user trying the same password in multiple applications in quick succession, or all users attempting to access the same application with incorrect passwords, may point to something more nefarious.

Similarly, activities such as out-of-hours system access and logins from unexpected locations should raise security flags.

To summarise, SIEM systems consolidate log events and use pattern analysis and some machine learning to identify whether there are anomalies that should be treated with suspicion. Findings are fed into the SOAR platforms for a defence response.

In effect, SIEM provides the intelligence, and SOAR decides what to do with it. Together, these tools represent the automation of two key stages of the security process – the information gathering and analysis, and the execution of the response.

Are SIEM and SOAR both required?

Organisations with a limited application and network estate, or where reporting is the main aim, will probably find SIEM is sufficient by itself.

But where there is a need to implement automated actions based on detected events, or when a consistent playbook of responses that must execute the same way every time is required, SOAR is becoming increasingly essential for the enterprise. For example, if a machine suddenly starts communicating with a server in an unintended location (outside its usual patterns), SOAR solutions can isolate that machine from critical systems, or disable specific ports from communication, depending on the nature of the threat.

Automation also enables the SOC team – which may not be very large – to focus on the remediation of actual incidents, or perform detailed analysis for which they might not have had time if they were required to monitor every single alert and take action within the organisation’s required service levels.

If SOAR tools are implemented correctly, they can pull information from multiple security platforms and tools operated by the organisation and can integrate threat intelligence platforms, SIEM systems, and user and entity behaviour analytics (UEBA) to automatically identify indicators of compromise (IoC) that might otherwise take an SOC analyst hours to identify.

This allows organisations to respond and stop suspicious or malicious behaviour before a human detects something is happening. The level of automation in a fully integrated system also removes large numbers of false positives from analytics and responses, saving valuable analyst time.

For all the advantages of automation, SIEM still has its place in an organisation. As well as capturing the event and log data required for SOAR input, the ability of SIEM tools to effortlessly process large amounts of data means they can be deployed in other business areas, including service desk ticketing metrics and forecasting, real-time key performance indicator (KPI) dashboards, and cross-platform compliance and risk reporting.

For example, identifying root causes or indicators of larger issues by triaging all tickets logged by a busy service desk can be difficult to complete when relying solely on human input. But a strong SIEM system can quickly pick up trends, correlate with other data sources and provide clear evidence that something requires further attention.

Investment decisions

Investment decisions also need to be based on the wider organisation and the security processes already established within it. For example, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) cyber security framework, which is rapidly being adopted as the industry standard for benchmarking, divides cyber security protection into five constituent elements – identify, protect, detect, respond, recover.

Based on current iterations, SIEM is better suited for measuring the effectiveness and efficiency of the identification and protection domains, while detect and respond capabilities are covered by SOAR. Tool selection is often based on the needs of the organisation and the capabilities it wishes to grow.

The activities and workload of the SOC is another useful pointer when an organisation is determining what additional support is required. If most time is spent investigating or responding to alerts captured by the SIEM tool, SOAR should certainly be considered.

But if the team is struggling to capture meaningful events, there is too much data to process, the tools are producing an overwhelming number of false positives, or incident management processes are yet to be defined, then enhancing the SIEM and its log collection and event management processes might be a wiser investment.

As with any IT security purchase, success will be determined by an organisation’s analysis of its current environment and understanding of the threat and risk landscape. Security professionals need to weigh up the advantages and disadvantages of automation versus manual processing and decide the value placed on each of the two stages.

Appreciation of the specific requirements guards against spending on capabilities that are not needed. Separate “best fit” systems can also be selected, resulting in an advanced solution in each area, rather than a single supplier model which potentially compromises on functionality.