It’s virtually impossible to drive a representative stake in the ground when it comes to trying to establish a position on Covid-19, especially in the UK. Fast-moving would be something of a euphemism. Just as tens of thousands of positive tests for the virus were “discovered” and subsequent contacts not followed up on, chaotic would not be an unfair description of the National Health Service (NHS) Test and Trace regime.

One key element of the programme, the UK’s contact-tracing app, has since its inception been dogged by similar negative publicity, mainly surrounding fundamental technical glitches and subsequent missed launch deadlines.

And looking at everything in the round, it’s no real surprise that many have basically written off the whole Test and Trace programme as a general failure, especially regarding the app for England and Wales, which national media reports upon hugely unfavourably. In particular, when compared with the apps that have launched in Germany and in particular the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland and Scotland, it is regarded as a very British failure.

But how fair is it to issue such a label to something that was just officially launched on 24 September? And getting under the hood of the long-last finished product reveals some surprising elements in its construction and some bold claims about its ability, especially as it stacks up against its Celtic counterparts. The Test and Trace programme may be some way from being as world-class as promised, but the contact-tracing app element is, says is developers, the most feature-rich product of its kind.

It’s worth looking at how we got where we are. The official app is a technological progression of the first version envisaged in April 2020, which was built using a much-criticised centralised database structure whose limitations were exposed in its first trial in April and May.

This early version received criticism for the aforementioned mishaps and technical issues, which led the Department of Health to make a U-turn on the underlying technology of the app, switching instead to a decentralised data collection model using Google and Apple application programming interface (API) technology.

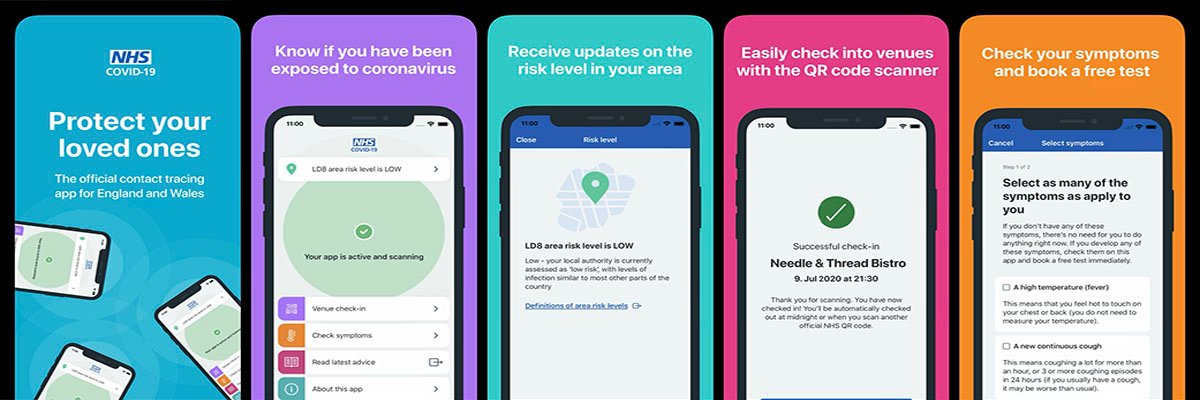

Available to smartphone users aged 16 and above in multiple languages, the app includes proximity tracing using Bluetooth Low Energy, risk alerts based on postcode district, QR check-in at venues, a symptom checker and test booking. The contact-tracing element of the app works by logging the amount of time users spend near other app users, and the distance between them, so it can alert users if they have been close to a person who later tests positive for the virus.

Working with major tech companies

In building the app, the digital innovation unit of the NHS (NHSX) worked closely with major tech companies, not just Google and Apple, but also VMware, in addition to teams in countries across the world using similar apps – such as those behind the very popular and successful German app. It also worked with scientists at the Alan Turing Institute and Oxford University, medical experts, privacy groups, at-risk communities, and the UK arm of the Swiss software firm Zühlke Engineering.

Zühlke took over the development of the product from VMware in July 2020, when the latter announced the end of work that had begun in March between its VMware Pivotal Labs division in partnership with NHSX when under direction from the innovation unit. VMware began work creating an app based on a centralised data model that was supported by a scalable back-end that could handle millions of records in a more secure and anonymous way.

VMware worked with Zühlke from the beginning of its involvement on all aspects of the technology behind the app, contradicting earlier reports that suggested Zühlke was brought in specifically to work on the decentralised version of the app. Sources close to the project said the plan was always that VMware would spearhead initial development of the app with Zühlke doing testing and assurance, with the Swiss firm taking over fully when ready to do so. Both firms worked on both the centralised and decentralised versions of the app from the inception of each.

Fast-forward to the launch, and it’s fair to say that Zühlke lead Wolfgang Emmerich is somewhat proud of the app that has been created. Emmerich is co-founder of the Swiss firm which began life 20 years ago, and has worked full-time in the UK since 2009, also fitting in being a professor of computing at University College London.

The company is named after Swiss engineer Gary Zühlke, a consulting engineer by trade whose career has included many projects in the world of medicine, including eye surgery and other medical devices. Such expertise was crucial in Zühlke being taken on-board for the contact-tracing project as the app is officially regarded as a medical device, one for which a CE mark has already been created.

Zühlke has also been a long-time supplier to the UK government, with branches such as HMRC, and also did the alpha and beta testing for the Gov.uk website. As a result, said Emmerich, the company knows how you’re meant to develop digital services for central government and the effect on internal processes.

Another key asset was that the firm also has a long-standing track record in mobile development in mission critical infrastructure, building, among other products, the UK mobile banking app for HSBC. This product was later spun out into 20 other territories.

Critical infrastructure

Another key element that provided credibility for work on the contact tracing project was that the HSBC mobile app was regarded legally as critical infrastructure with very stringent security and availability requirements, as well as able to scale to tens of millions of users.

The Zühlke team was with the NHS right from the start. A former colleague of Emmerich was a chief advisor on cyber security for Patrick Vallance, chief scientific adviser to the UK government, and this led to an introduction with NHSX chief executive Matthew Gould when the project was just about to kick off its first step and [asked if] they wanted help in independent assurance to ascertain that the development was going in the right direction.

This initial input was limited, and excluded the initial specifications and timeline. “We basically checked and validated that the app, but it would not work in certain circumstances,” said Emmerich. “So we bid for, and won, the support contract for the first app, and we used that contract to build the second app. For that we very much had input into the product roadmap and what the features of the app looked like.”

The first app has been widely criticised as a failure, but to Emmerich, the original concept of having an app that could support a centralised data structure from which the NHS could leverage insight in the fight against Covid-19 was essentially a good idea. In February 2020, he would have been in favour of it, but he added that there are trade-offs meaning other people might not necessarily agree.

“There’s a lot of people who are concerned about privacy or sensitive information,” he said. “They don’t necessarily think it’s a good idea for the government to collect contact traces. Ultimately, the first app was not successful because of different angles on trade-off decisions in battery consumption versus accuracy and privacy.”

“So, the reason why the first step wasn’t successful is fundamentally because Apple was concerned about battery life, particularly of older phones, so that it would prevent apps from activating the Bluetooth stack in the background. Bluetooth ping sending and receiving Bluetooth beacon messages is an expensive operation as far as power is concerned, and Apple was not willing to give up that restriction. That ultimately meant that you had to fight the operating system, and ultimately that fight wasn’t successful in getting the app to work in the background.

“If I was in Apple’s shoes I would have made exactly the same decision, because their products are judged by customers on battery life, and if an app depletes the battery life unduly, even in the background while users are not aware the app is actually doing that, then that ultimately reflects poorly on Apple’s products.”

Does this mean the app designers were ultimately working on unfeasible and unfair timelines in the rush to get the app out the door? Emmerich broadly agreed.

“In our experience, development is never in a straight line,” he said. “We are very strong proponents of using lean and agile techniques with the express advantage of failing early and failing quickly. I think we actually failed early, and unlike France, for example, where they knew that the app was not really properly functioning, we didn’t still release it. We took our ethos seriously; that is we are engineers who are building products that are fit for purpose, and this first app was not possible to be fit for purpose. It was certainly not possible to have it as a medical device. We would have to ascertain that it actually worked in all circumstances. And as a result, it just had to go.”

Zühlke encountered no further bumps in moving to a decentralised model, even though the nature of using the API and switching meant it wasn’t able to reuse much code – mainly because their backends had to be completely different. It did reuse some UX designs and styles, but ultimately Zühlke built the new app from scratch in six weeks. Such a timeline, it should be emphasised, is completely out of the ordinary in app design – especially for a medical device.

Emmerich has called the result one of the best contact-tracing apps in the world; the product of working with other developers from around the world, reusing material from companies including NearForm – the creator of the Irish and Scottish apps, as well as now apps for a number of states in the North East of the US – as well as the SAP developers involved in the successful German product, and also material from Russia and that from the developers of the New Zealand app.

“That has enabled us to build a very feature-rich app in a very short period of time,” he said. “We’ve done a comparison of all the apps that are out in the world, and I can argue, based on the feature comparison we will release in England and Wales, the feature-richest app in the world.

“And we will not just have the features that they have in Northern Ireland, and in Germany, but it will also have features that actually aimed to give guidance individually to the users of the app. This includes, for example, a risk score based on the infection data broken down by postcode.”

Some of the comparisons seem surprising. The NHSX app’s Bluetooth contract-tracing is something that the New Zealand app does not have. But it does have, like the UK version, QR code venue check-ins which have been very successful.

Data security and privacy

Among the key challenges has naturally been data security and privacy, while ensuring optimum accessibility. In this regard, Emmerich emphasised the work his team has undertaken with the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), which tested attacks on both the underlying cloud infrastructure and the app. Regarding accessibility, given it is an NHS product, the app needs to have, he said, higher-than-usual requirements on accessibility.

It had to meet web accessibility requiring a certain amount of rework to ensue voice mechanisms and localisation. The app has been released in 10 languages. In addition to English and Welsh, the NHS felt the app should be usable to people who don’t necessarily speak the two languages, particularly in communities in the north of England.

Looking to future developments, Zühlke is working with the Engineering Institute to improve the accuracy of the estimation of distance, and has even made suggestions to Google and Apple regarding the API, which have since emerged in upgrades to the two companies’ operating systems for devices.

The key, though, is to drive adoption. In this, Emmerich said that even in the trial of the centralised app of the Isle of Wight, adoption rates were “really, really encouragingly high”, at around 55%-60%, and that very important lessons were learned that have been fed back into subsequent development.

As a key measure of the success of Zühlke, the company’s initial six-month contract that was due to expire in November has been extended for another six months. This will see what is described as a “fairly aggressive” roadmap of further improvements and features, including offering a more personalised risk score, known as a “Geiger counter” feature, based on how many Bluetooth hits a person receives from others.

“You can measure how many different phones you see and how often you see them, and you can feed that back until people are really socially distancing,” said Emmerich. “We can give people various visualisations of how risky a life people lead to influence their behaviour.”

Alarming plans

Yet despite the clear benefits of this, the feature has already generated misgivings. BCS, the Chartered Institute for IT, has described plans to use the app to rate users’ lifestyles for risk as “alarming” and needing clarity, adding that such algorithmic scoring approaches are often inaccurate and can have unintended side effects.

Adam Leon Smith, who chairs the Software Testing Group for BCS, said: “Some data is being stored unencrypted, locally. This isn’t of great concern as it appears to be just system configuration data, with the sensitive data being stored by Google and Apple.

However, as the functionality is expanded to include things like personal risk scores, this needs to be encrypted, and I’m keen to see this isn’t passed to the developer’s servers to establish a centralised tracking system by the backdoor. There are security issues with using Bluetooth in this way. It remains possible for attackers to manipulate the behaviour of the system to give incorrect information to users, however this has been made more challenging through various means.”

What is far less contentious is international interoperability being on the roadmap. This means that if a person travels to Ireland or Germany, for example, the app will notify users if a local person they’ve been exposed to tests positive. The NHSX app is also part of the EU Gateway project which, in September 2020, announced trails interconnecting the backend servers of the official apps from the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Ireland and Latvia.

Developed and set up by T-Systems and SAP – the two bodies responsible for the development of the German app, which by July 2020, barely a month after initial introduction, had been downloaded 15.8 million times – the gateway is designed to ensure that apps work seamlessly across borders and hence users will only need to install one app, even if they travel abroad. In addition to Zühlke, Ireland’s NearForm is a key player, handling the technical aspects on behalf of the Irish health authorities.

Reflecting on the project to date, Emmerich said he’s proud of what he and his team have achieved, especially given the time constraints. He noted that after seeing the time sheets of some people on the team, he’s actually worried about their health, and when assessing whether he would have done anything differently, he said he would have not let that happen by increasing the team at his disposal.

To date, it looks like the app has been a success, with over 10 million downloads in its first three days of availability. However, early teething troubles were identified in entering test results for hospitals in England, although these issues were dealt with in a matter of days. But while that has been addressed, it exemplifies the success of the app is not just contingent on its technical capabilities, but rather how it fits into and adds value to the Test and Trace programme as a whole. This is where having the most feature-rich app could prove rather handy.